How Schools Should Work

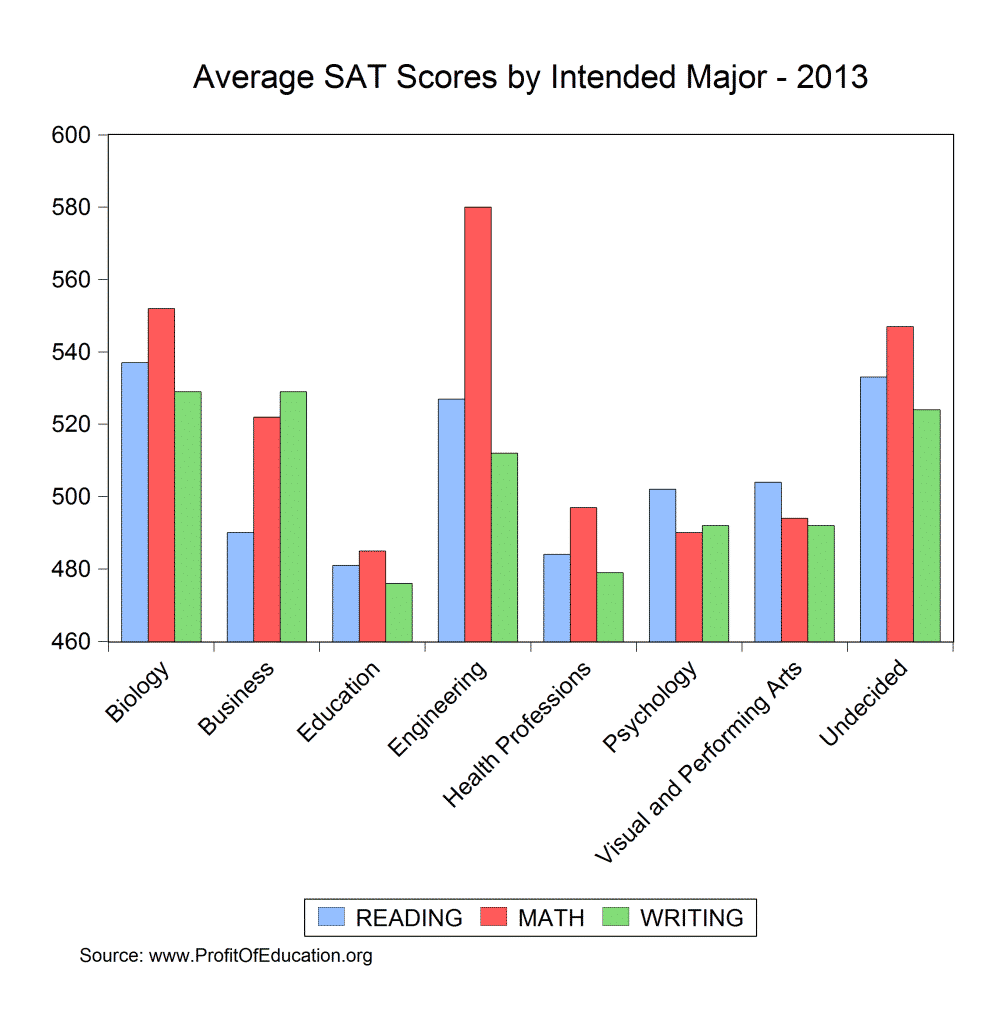

It’s no secret that our public school system has had unimpressive results. We rank 38th in math skills, 25th in scientific literacy and 24th in reading literacy out of 71 competitive countries worldwide. There’s no shortage of explanations as to why. Many point to cultural issues — home situations for students and single parent households. Many point to the origins of the public school system itself from industrial factory origins. Several point to the compromises made at the behest of teacher’s unions to protect their staff at the expense of students. Many point out that education majors have some of the lowest overall SAT scores out of all college attendees.

There are a multitude of other factors contributing to the underperformance of educational systems in this country. It’s a sticky web of correlation and causation, but defining the problem is what’s most necessary. The problem, in a nutshell, is this:

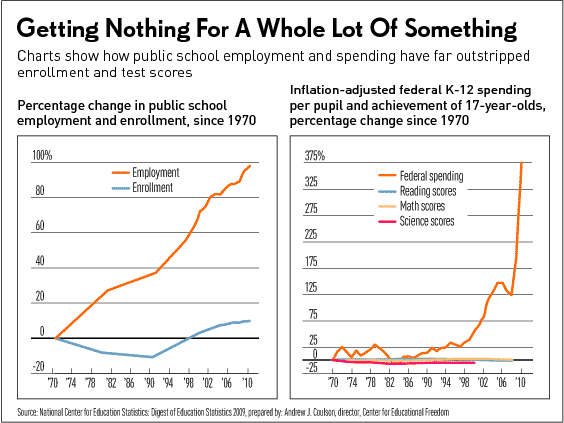

For all the research done into this space, all the solutions pioneered and championed by politicians and all the money spent lobbying to get those solutions implemented has done, for lack of a better word, fuck all, worse than nothing. Keep in mind the graph above shows only spending on approved endeavors, not spending on research, publicity, and all the other inherit costs of getting public momentum on the side of potential changes, necessary for a public entity like the public education behemoth.

It’s clear to me that changing the system of how experiments get implemented into the education system to be more dynamic and agile is necessary. If, every time, we want to experiment on something like pre-K education only to find it’s a complete waste of time and money, we have to spend 50 years (Head Start originated in 1965, can you believe it?) and millions of dollars, then we’re not going to find the answers quickly enough to become competitive. It’s my contention that schools need to be opened up to further competition so that experiments can be approved and implemented much faster to expedite the acquisition of results-based data. That’s why I’m a proponent of school choice — more than anything it’s because it frees schools to compete with one another about how to drive up test scores as well as the intangible benefits of school like socialization. Will paying teachers more attract smarter teachers into the field? Will integrating technology help keep kids engaged? All these hypotheses and more, coming to a school near you without 50 years of debate or the inefficient use of taxpayer dollars.

But this isn’t an article about school choice. I’m just providing context here. This is an article about what I think schools should look like in the 21st century. It’s also not a prescription, it’s my contribution to the conversation.

I believe that schools in the 21st century should replace the the factory-based classroom system which segments students into peer groups based on age which are then preached to by an underpaid teacher who, statistically, didn’t do well in school themselves with a community center model with a pick-and-choose progression system that is customized to children’s unique learning styles. Let me explain how this would work.

Your child has a teacher assigned to them for the year. Let’s say, for example, the year is 5th grade. Your child has a number of minimum educational requirements at this age. They must achieve a certain level of reading, writing, math and science skill, must participate in socialization programs, and must pursue at least two areas of interest (i.e. animals or music). The teacher offers a menu of approved methods to achieve the expected mastery of these skills – tutors, lecture series, self-study, online classes, etc., with the expectation that the student will be able to pass regular benchmarks. Though there are minimum requirements, we expect every child to be moving forward. If they get ahead of the game, they can take a less intensive maintenance course in that subject to make space for more extracurriculars or continue pushing forward. Age is de-emphasized. Skill is emphasized. Age-based socialization can be provided without being tied to skills, i.e. a greater emphasis on interest-based clubs.

We know, from Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences, that the learning styles of children are different and wildly individual.

This is a well-accepted theory, though there are some detractors, and, if you think about it, it’s quite intuitively true. So what occurs now in schools, a one size fits all 12 year lecture series, is fantastic for verbal learners. Others will become bored. Furthermore, not all students learn best from (largely female) adult authority figures. Personally, I learn best from cute girls who find me very charming, but that’s just me. They keep my attention. Some people can be left alone with a book and come back with all its knowledge, some people need to have someone sit them down and explain concepts as they relate to personal interests. My idea functions on 3 main points.

1. Integrate Learning Styles into the School Paradigm

By providing a menu of different class-styles that achieve the same ends, we allow students and parents to self-select what is best for their child. If they know their child learns great from a male mentor ‘hardass coach’ type, and their attention is kept if they’re able to throw a ball around, you can enroll them in a math class that relates math and sports, tackling the child’s interest while also achieving the necessary mastery of math skills for that year. I’ll relate this to a point from my own life — I’m a leg twitcher. Sitting in a class for hours on end, I would twitch my leg endlessly to burn off excess energy — I used to say it was ‘my thinking motor’. It wasn’t until grad school, where I could behave essentially however I wanted in classes, that I found I retained information better and had much higher engagement if I was able to walk around and toss a ball while the class was going on. Obviously other students may have found this distracting, but the one-size-fits-all lecture model also disadvantages people like me who need to move around.

2. Integrate New Technology into Teaching

We live in an age where online resources can provide as good, if not better, information to students. This would be perfect for kids who learn best from a solitary learning style, but also helps connect kids from around the world. We don’t want kids to become isolated, which is why socialization activities should be required at all ages, but is a kid stuck in a classroom with 40 other kids while a teacher talks nonstop really adequate socialization? I was raised by a teacher and have known a lot of teachers in my life and it’s amazed me how little teachers, in general, know about technology and how low their comfort level is, especially when technology is so well-suited to improving education in general. From a practical, real world standpoint, if teachers aren’t trained in technology in college, and technologists aren’t participating in education, the technological breakthroughs that can take our system to the next level will never come. We need technological learning to be a component of the system.

3. Separate Skills from Age and Socialization

One of the problems with the current education system is it tries to do too much at once in an inflexible way. One of these things is that it purports to teach socialization at the same time it’s teaching skills. It doesn’t do a very good job of either. Breaking kids up into age groups isn’t the best way to handle socialization. In the real world, past a certain age, you aren’t broken up into age groups. Perhaps, roughly same-age cohorts, but 25 year olds will be sharing job titles with 30 year olds commonly. Even by college it’s a bit off — a college freshman could commonly be between 16 and 22 years old. I think it’s more important to socialize by interest with a rough guideline for age group, i.e. the primary school music club which spans ages 13-16. Personally, I skipped a grade and went to college at 16. One of my discoveries from that experience is that people aren’t well-socialized with people outside of their age group. I was expected to act at the maturity level of a 19 or 20 year old, and 19 and 20 year olds didn’t have a strong grasp on how to behave around a 16 year old. So the socialization experience was a cost of skipping ahead — but really, it’s a no-win situation. If I hadn’t skipped ahead I would have been with kids my own age but disdainful and bored.

How do you think education should look in the 21st century? Try to forget about what we have now. If you were just making it up, as if it had never been attempted, how do you think you would do it?

I want to add something else random here, just to finish off — I think in the 21st century foreign language from an early age should be a core component of the school system, right alongside math, science, English and history. In our quickly globalizing world, with AI on the horizon, jobs which connect people are going to be the future, which means, arts, humanities, and more than anything, being able to speak a foreign language. If I had a kid right now, I would make it a priority to ensure they speak Spanish, German or French and at least one Asian language (Chinese/Japanese/Korean).